Note: Much of the information concerning the LCP comes from : The Other Desert War, by John W. Gordon. For a full treatment you are advised strongly to read his book.

Light Car Patrols, World War I

The Long Range Desert Group was the brain child of Major Ralph Bagnold, Royal Signal Corps. Bagnold was an officer serving in Egypt before the outbreak of World War II. One of his favorite past times was taking extended trips into the Sahara with some fellow officers. By 1939, he and his fellow travelers had perfected many of the modes of crossing the desert later used by the LRDG. But to understand Bagnold and the LRDG you really need to go back to 1916.

Bagnold was aware of the exploits of the Light Car Patrols (LCP) conducted by the British and Australians during their campaigns against the Senussi and later the Turks during World War I. In all 15 such units were working at any given time behind enemy lines, providing a potent strike force against Britain's enemies.

Italy occupied Libya in 1911 and from that moment, the Senussi, an Islamic Religious sect began waging a guerilla war against them. With the outbreak of World War I, Italy allied itself with Britain and France. Turkey allied itself with Germany and the Austria-Hungry Empire. Germany and the Turks both saw in the Senussi the possibility of opening a second front against the British and Italians which would make it quite impossible for them to wage an effective campaign in Damascus and Palestine. With some financial and military support the Turks were able to to get the Senussi to join the fight against the British.

The Senussi were expert raiders who could seemingly strike from nowhere and then disappear into the nothingness of the Sahara. However they were incapable of holding ground. The usual method of attack was on camel back, which meant they were vulnerable to artillery, and machine gun fire, if you could bring it against them.

The British as well as all the colonial powers of the time were well aware of the capabilities of camel mounted troops and quickly organized a camel mounted regiment. But the then commander of the British in Egypt, General Sir Archibald Murray, knew such a regiment would have serious limitations without artillery or machine guns support. This meant that engage the Senussi with Colonial Camel troops would lead to devastiting losses. Simply put: the Senussi were better fighters on camel back and they knew the desert. More firepower and mobility was needed.

The answer came from the use of armored cars, specifically the Rolls-Royce Armoured Cars of the Royal Naval Air Service. Then First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill thought the armoured cars would come in handy for scouting and searching for downed navy pilots. But the armoured cars could not keep pace with the camels and were quick to bog down over long stretches in the desert. What was needed was a lighter more reliable car that could move swiftly and carry the additional fire power that the camels lacked. This was the modified Ford Model T and gave birth to the Light Car Patrols.

The LCP patrols operated in modified Ford Model T's armed with Lewis machine guns. Other modifications included 3 1/2 inch wide desert tires, radiator condensers mounted on the running boards, and primitive sun compasses on the dashboard. Most of these adaptions were the brain child of the fifty year old British archaeologist and desert explorer, Dr. John Ball. Ball who had been working in the Government Survey Office in Cairo at the time.

By using a combined force of Light Car Patrols, the Armoured Machine Gun Motor Battery (Rolls Royce Armoured Cars), Camel Corps, and BE2 fighters of No. 17 Squadron, the British were able to defeat the Senussi. Of course this is partially attributed to the leader of the Senussi, Sayed Ahmed, listening to his Turkish Military Advisor, Ja'Far Pasha who felt the Senussi should hold key locations to prevent the British and Italians from moving.

Eventually the LCPs would corner the senussi in their stronghold at Siwa oasis, and through some luck and pure tenacity drive the Senussi out of the oasis and virtually eliminate them as a potential threat. From Libya the LCP and the the rest of the unit would be deployed to Palestine and receive a new commander "Sir Edmund "Bull" Allenby.

For the purpose of the LRDG, what is probably more important is the actions of the LCP. The operation at Siwa did had been observed by Lt. Col. Archibald Wavell, the man who would later give Bagnold the green light for the LRDG!

The typical LCP patrol consisted of two officers and twelve other ranks operating in five or six cars. With the end of World War I the LCP was disbanded, however the lessons were not forgotten. The British, French and Italians realized the need to continue to employ some form of motorized response to the numerous desert uprisings that occurred during the 1920's and 1930's. While both the British and French made strides at integrating a land and air response to Arab raiders The Italians went still further and formed a self contained unit with motorized scouts, armored cars and aircraft. The unit was so integrated that the ground commanders had to be licensed pilots! This unit was the Auto Saharan, and they were once again fighting the Senussi and other Arab tribes in Libya.

Check here for place to find more about the Light Car Patrols

The Coming Desert War

At the outset of WWII the British were in Egypt and the Suez Canal, which acted as a crucial link to much of the British Empire was of the utmost strategic importance. It was also seen as important to Italy and Germany. With the occupation of Libya by now Fascist Italy, the threat to the Empire was enormous.

Fortunately, for Britain, Ralph Bagnold and other familiar names to the LRDG (Pat Clayton, Bill Kennedy Shaw, Guy Prendergast, to name a few) had been avid desert explorers between the wars and had spent numerous hours of their free time and personal money building on the methods learned by the LCP in getting around the desert. Many of the lessons learned in this peace time pass-time would be directly applied to the mission of the LRDG. Among other things, Bagnold had made major improvements on the Sun Compass, which with these improvements, was patented by him, and with the aid of the Royal Geographic Society had managed to actually cross the Great sand Sea on several occasions using Ford Model A trucks. A feat considered impossible by just about every desert explorer!

Capt. Patrick Clayton

Leader of the

first LRPU patrol

Bagnold was aware of the dangers posed by the Italians in Libya. During one expedition, he ran into a boastful lieutenant of the Auto Saharan Company near the Kufra. The Auto saharan company and Bagnold's party spent a few days together and Bagnold consider the Italians polite, even gracious host. But he took note when the leader of the company boasted of how easy it would be for his company to make a raid across Egypt and blow up dams along the Nile and cut lines of communication and in general cripple the British Army in Egypt. Bagnold did not consider the comment boastful pride but a truthful account of the capabilities of the Auto Saharan.

Before the outbreak of the war in 1939 proposed that the British Army form a long range patrolling unit to spy on its neighbors to the west. His proposal was roundly dismissed as being diplomatically unsound as well as physically impossible. Most of the British senior staff felt it was impossible to operate motor vehicles through the uncharted desert. They all seemed to feel their was no need or no feasible way to accurately chart the desert. Furthermore it was felt that any long range reconnaissance could be accomplished with aircraft.

The War Begins and the birth of the LRPs.

As luck would have it, Bagnold had retired as a major after 20 years of service shortly before the war began. He was living in England but was recalled to duty. As one can suspect, because of his knowledge of the desert, the British Army decided to post him in Kenya! Fortunately for the British, his ship collided with another vessel in the Suez Canal and he wound up in Alexandria, Egypt. By this time Field Marshall Archibald Wavell was in command of the Middle East. Wavell, who was aware of Bagnold's past desert explorations has Bagnold assigned to the 7th Armoured Division(Desert Rats). Bagnold did not pitch his idea for long range patrols right away.In time, but in time he began to propose such plans with his immediate commander. While his immediate commander was keen on the idea higher commanders were not. Eventually however, Bagnold went around the chain of command and with some help got his proposal in Wavell's hands. The proposal was met with enthusiasm and a short deadline of six weeks to get the unit operational. Bagnold was transferred to Wavell's headquarters. The unit was called the "Long Range Patrols" or Long Range Patrol Units.

Bagnold was given a free hand to call for volunteers and decided early on to look for more robust "colonial forces" that were coming into theater, assuming they would be more self reliant than British Units. His first choice were Australians, assuming the arid outback region would have made them acclimated to a region like the Sahara. Unfortunately the Australian Divisional commander did not want his men be led by a British Officer. The New Zealanders were approached next. Their commander, Lt. gen Bernard Freyberg had won the Victory Cross in WWI and was a colleague of Wavell. Within a few days Bagnold had his volunteers and they were considered the best that the Division had to offer.

The initial patrol was led by Pat Clayton, one of Bagnold's friends. What they found was a demoralized army in no hurry to fight. The information proved accurate and was instrumental in the campaign that followed. Wavell realized he was in no immediate danger and informed London that 2RTR and 7RTR could take a longer safer passage to Egypt instead of being rushed through hostile waters.

A New Name and New Patrols.

With the success of the initial patrol and some following raiding missions,Wavell immediately authorized the doubling of size of the LRP and the unit took on its new name, the Long Range Desert Group, LRDG. Unfortunately the New Zealand division could not spare more men and Bagnold actually had to give a few of the originals back to the division!

Bagnold was forced to look else where and that elsewhere was once again newly arriving divisions. Among those arriving were the Coldstream Guards and Scots Guards, two of the Britain's finest division and numerous Yeomanry units. Yeomanry were mounted territorial or reserve units. Bagnold realized that the various backgrounds of the professional and the part time, and the colonial may not be a good mix so instead of integrated the new men into the New Zealand patrols he organized two new patrols "G" for Guards and "Y" for Yeomanry. "W" patrol was gone but the New Zealander still had "R" and "T" patrol. The letters coming from Maori words used on their vehicles. Later another patrol would be raised from the southern area of the colony of Rhodesia and this patrol would take the letter "S" for south.

The men were not drawn based on physical attributes as much as they were for their mental stability and stamina. Not only did the men of the LRDG have to cope with long stretches of loneliness, harsh weather conditions, and danger, but they had to be intelligent.

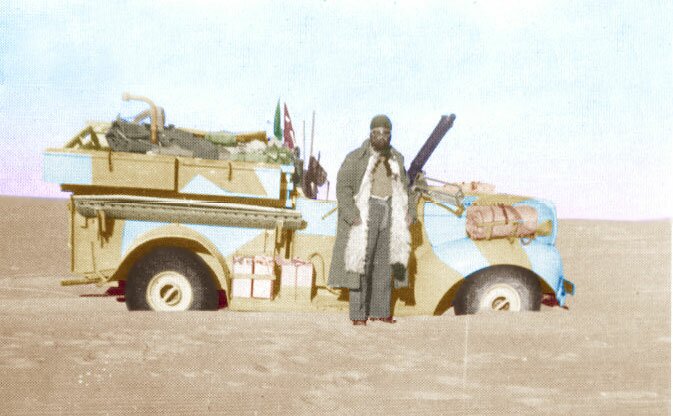

Ford truck used by the LRPU/LRDG

While physical toughness was a necessary, the troopers had to work well with others while at the same time be self reliant. Each trooper needed to become a specialist in some aspect of the LRDG mission. Men were trained to be medics, navigators, fitters (mechanics), radio operators, etc. Besides being a specialist in one area they were cross trained in the event they had to take over for someone else. In short, you had to be competent in every aspect of the mission but be expert in one or two areas. All the members, officers and other ranks were expected to pull their weight and be cross trained. All member were expected to know all the weapons employed by the LRDG. Many of these attributes would live on in such organizations as the SAS and the U.S. Army Special Forces (Green Berets) but the concept was novel in a modern army when it was introduced by the LRDG.

The LRDG also operated with other special forces such as the SAS, SIG (Special Interrogation Group), and the Commandos. They also operated with individuals from British Intelligence.

See also: LRDG Mission